01. The Basics

"The irony, of course, is that, while I say I like 'right' answers, in reality there seldom is a definitive answer. Training and competing are less an exact science and more an endless puzzle; they are a creative process of trial and error - and a process I enjoy, even though I know that the correct answer one season can be the wrong one the following year" - Chris Hoy

Athletes in many sporting endeavours can be classed into four broad groups; novices, intermediates, advanced and elite athletes. The type of programming for each is not the same, the sort of training that will improve an elite rider may cost a novice precious time, for example. We're going to discuss some basics here before we go into any details, so please bear with us. It won't take too long and this is valuable stuff.

We'll be drawing on some excellent work done by Mark Rippetoe and Lon Kilgore here to explain the four groups, and then we'll concentrate on novices and intermediates. If you're an advanced or elite sprinter, you don't need this book, you already have expert coaches with decades of experience and complex plans to eek out the last few percent of your abilities, but feel free to read on all the same, if that's you! We also recommend familiarity with Charlie Frances' work on periodisation.

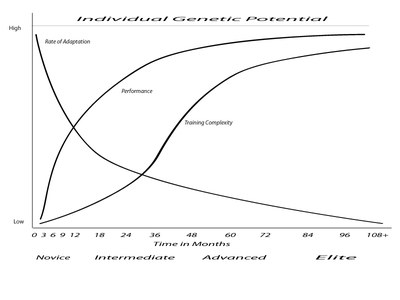

Firstly, what is a novice or an intermediate, an advanced or an elite sprinter? We're going to use a chart that we're unashamedly stealing from Rippetoe and Kilgore's excellent "Practical Programming for Strength Training, 2nd edition" (with their permission, of course!). They define these levels by performance improvements and training complexity against time and not on results, although an elite rider would expect to be getting world-class results, so that's another way to look at it and is valid, but not for the use we're looking at, which is program design. Many cycling books and indeed many training books and material skips past the novice stage which we think is a mistake, it is novices that gain fastest, and who establish good motor patterns, skills and habits, and who, most likely if you're reading this, you are. All that as it may be, here's the overview for your consideration :

As you can see, novices gain performance very quickly, using very simple programming - sprint. Do lots of sprints, repeat ... As long as they're the right sort of sprints, this is fine and is all that is needed to enhance performance - there's no need to split things up into monthly blocks of this and that and so forth, we'll leave that for the intermediates and advanced sprinters, who do need more complexity. When you start out, keep it simple. Sprint, rest, recover, refuel, repeat. This phase can last for months, as it can in the gym with your lifting, upon which this method is based. We want to milk this for all it's worth while we can, to use your time as efficiently as possible. Complexity in training plans at this early novice stage, we think, will slow down your progress. We're sprinters, we want to do things quickly ... BUT, here's a biggie. We don't do much and we rest lots. Studies have shown that even doing "sprint" training, if done too much, can reduce sprint performance. How much is too much is an excellent question, but for beginners and intermediates, two to three sprint sessions a week is ample to see consistent improvements in performance. Don't overdo it!

So how do we design a program for a novice sprinter? We're glad you asked.

First, we need to identify the needs of sprint events, and then write programs to develop our sprinters along those ways.

It is the opinion of the authors that (and this is opinion, not fact) sprinters mainly need the following things :

High absolute peak power levels

High peak power to weight ratios

Ability to generate high power at high cadences for short periods of time

Ability to start from a low speed and accelerate quickly

Ability to produce high power outputs for around 15-20 seconds, up to around 35 seconds at most

Bike handing skills and tactical ability

Cunning

Missing from that list is a high level of aerobic fitness. This is because aerobic, or "LSD" (Long, slow distance) training has a negative effect on peak strength and peak power outputs. We need to be fit for our sport. the following graph helps explain this a little, and is from FIT, by Dr Lon Kilgore, Dr. Michael Hartman and Justin Lascek

So how do we train these things?

To be powerful, you have to be strong. It's trivial, but to lift 100kg quickly, you have to be able to lift 100kg, or push it through your pedals, or however you want to express the need to be strong. Sprinters are STRONG. You can't be powerful without being strong. You can be strong without being powerful, for sure, but we're not going to be doing nothing but slow lifts in the gym, but we will be doing them, because we need to be strong. Our enduro friends don't need to be anything like as strong as us, they can change gears to keep their torque loads low when they're racing on their road bikes and acceleration plays much less of a part in a pursuit than it does in a sprint or a team sprint. We have to push big gears hard to get started. The stuff you read about cyclists not needing great strength applies to enduros (if it applies) but most certainly not to sprinters.

So ... We're going to make our sprinters strong, powerful, and teach them to rev, and to rev at high power outputs, and to rev for up to 35 seconds and to rev for 35 seconds putting out power. Simple? Yes, but there's a lot of things to do. Hopefully you're on board, the next part of this book will be some sample templates to consider.